Scroll to:

Five years of the Genomas Brasil Program: advancing genomics and precision health within Brazil’s unified health system

https://doi.org/10.47093/3034-4700.2025.2.3.41-59

Abstract

This study aimed to assess the implementation of the Brazilian National Program for Genomics and Precision Public Health (GenBR) over its initial five years, identifying key achievements, challenges, and lessons for integrating genomics into public health systems in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Established by Ministerial Ordinance GM/MS No. 1,949 on August 4, 2020, GenBR aims to lay the foundation for genomics and precision health within Brazil’s Unified Health System. Its primary goals include advancing science and technology countrywide, fostering the development of a national genomics industry, and conducting proof-ofconcept studies to assess the practical application of precision health in public healthcare. By August 2025, over 250 research projects had been funded in 19 of the country’s 27 federative units, across a range of areas, including oncological, rare, cardiovascular, infectious, neurological, and non-communicable diseases, as well as population genomics and precision health. Financial investments had exceeded BRL 1 billion, funding the sequencing of 67,000 samples. Nine large-scale genomics research projects associated with the Program have contributed to generating whole-genome data from 45,910 individuals. Moreover, four public calls have selected 209 research projects led by science and technology institutions located across all regions of Brazil. GenBR offers key lessons for LMICs seeking to implement genomics in public health, particularly in contexts marked by population diversity, infrastructure asymmetries, and fiscal constraints. Findings highlight the importance of sustained political commitment, inclusive governance, and long-term planning for building national genomic capacity and advancing health equity.

Keywords

For citations:

Araújo de França G., Lupatini E., Rocha R., Toledo R., Figueiredo G., Gonçalves C., Machado I., Anzolin A., Gontijo C., Vidal J., Ribeiro A., Freitas M., De Negri F. Five years of the Genomas Brasil Program: advancing genomics and precision health within Brazil’s unified health system. The BRICS Health Journal. 2025;2(3):41-59. https://doi.org/10.47093/3034-4700.2025.2.3.41-59

Introduction

From the late 20th century onward, Brazil underwent profound demographic and epidemiological transformations that brought new demands to its public health system and research agenda. Declining fertility and rising life expectancy led to rapid population aging, while infectious disease mortality fell sharply due to vaccination, sanitation, and primary care improvements [1]. Non-communicable diseases became dominant, exposing the need for more personalized, preventive, and data-driven health strategies within the Unified Health System (In Portuguese: Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS) [2].

Despite major advances in genomics and precision medicine globally during the first two decades of the 21st century, Brazil lacked a coordinated national framework to translate these innovations into practice within SUS. The Brazilian population, marked by extensive genetic admixture and rich sociocultural diversity, has been significantly underrepresented in international genomic databases, which remain predominantly composed of individuals of European ancestry [3]. This lack of representation has limited the relevance and applicability of emerging diagnostic, predictive, and therapeutic tools to the Brazilian context. These limitations were further compounded by the absence of a national infrastructure for high-throughput genomic sequencing, a shortage of professionals trained in genomics and data science, and insufficient investment in health innovation ecosystems essential for advancing precision health initiatives [4].

In response to these intersecting challenges, the Brazilian Ministry of Health (MoH) launched in 2020 the National Genomics and Precision Public Health Program, also known as Genomas Brasil (In Portuguese: Programa Nacional de Genômica e Saúde Pública de Precisão, henceforth GenBR). As a strategic policy initiative, the Program aims to advance genomic and precision health, focusing on equity, scientific sovereignty, and innovation within the SUS.

GenBR aligns with broader national development frameworks, including the National Policy for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health (In Portuguese: Política Nacional de Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação em Saúde)1. More recently, the Program underwent a redesign considering the New Brazilian Industry strategy and the National Strategy for the Development of the Health Economic-Industrial Complex (In Portuguese: Complexo Econômico-Industrial da Saúde, CEIS), established by Decree No. 11,715/2023.

This study aimed to assess the implementation of GenBR over its initial five years, identifying key achievements, challenges, and lessons for integrating genomics into public health systems in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Materials and methods

This narrative review analyzes the five-year implementation of GenBR, covering the period from its inception in August 2020 to August 2025. The bibliographic search covered this timeframe, and data analysis applied Bardin’s content analysis technique2.

In Stage 1 (pre-analysis), the authors identified and selected relevant documents and scientific articles from peer-reviewed journal databases, institutional websites, and official federal government publications. They searched PubMed/MEDLINE without restrictions on language or publication date, using the following keywords: “genomics”, “precision health”, “personalized medicine”, “genome sequencing”, and “Genomas Brasil”. In Stage 2 (material exploration), the research team reviewed selected documents and extracted relevant information to support the development of analytical categories. Finally, in Stage 3 (data processing and interpretation), they critically analyzed and synthesized the content within each category, with a focus on the most significant findings related to the Program’s implementation and its broader policy context.

Results

Historical context

Brazil is geographically and socioeconomically divided into five major regions (North, Northeast, Central-West, Southeast, and South), which are highly heterogeneous with respect to social, economic, environmental, and demographic factors [5]. With an estimated population of 212.6 million, Brazil is the most genetically admixed country in the world [3]. Due to European colonization between the 15th and 20th centuries, Brazil received millions of European immigrants and, through the transatlantic slave trade, millions of forcibly displaced Africans from diverse ethnic backgrounds3. Estimates suggest that European contact led to the decimation of over 10 million Indigenous people, with effective population declines ranging from 83% to 98%, depending on the region [6].

External and internal migration processes have shaped Brazil’s demographic distribution. Population is concentrated in the Southeast region (41.7%), followed by the Northeast (26.9%), and South (14.6%) regions. African ancestry is more prevalent in the Northeast, while Indigenous ancestry is more prominent in the North. Moreover, densely populated urban centers, such as São Paulo city, exhibit significant ancestral diversity [7]. In this context, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of individuals from Brazil’s highly admixed population provides a unique opportunity to explore the relationship between genetic variation and health outcomes [8].

Advances in genomic sequencing, initiated by the landmark Human Genome Project [9], have expanded scientific understanding of human genetic diversity and encouraged the development of numerous national and international initiatives. Recognizing the potential of personalized healthcare and the development of therapeutics aligned with population-specific genetic profiles, many high-income countries have invested heavily in national genomics programs and their clinical implementation. At the forefront of these efforts, the United Kingdom’s 100,000 Genomes Project [10], led by the National Health Service, and the United States’ All of Us Research Program [11], coordinated by the National Institutes of Health, have consolidated the clinical use of genomics by establishing national genomic service infrastructures and shared databases accessible to academia and industry. Both initiatives have become global benchmarks, inspiring similar programs worldwide, including Genomic Medicine France [12], the Qatar Genome Program [13], Australian Genomics [14], the Saudi Human Genome Program [15], the Chinese Millionome Database Project [16], and FinnGen [17], among others.

In the Global South, genomic initiatives are diverse and context-specific, each aiming to address the unique health needs and challenges of their regions [18]. Pioneer in Brazil, the Brazilian Initiative on Precision Medicine (BIPMed), established in 2015, aimed to facilitate precision medicine implementation through collaborative data sharing and stakeholder engagement. However, BIPMed was a local initiative that primarily involved participants from Brazil’s Southeast region, and employed whole-exome sequencing and single nucleotide polymorphism arrays rather than WGS [19].

These efforts are driven by the potential to transform the diagnosis, treatment, and management of genetic conditions, enhancing disease risk mapping across varied populations and identifying novel genetic targets for therapeutic development [20][21].

The underrepresentation of diverse ancestries remains a major barrier to achieving equitable outcomes in genomic research and medicine. Most genomic data in databases and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are of European ancestry, corresponding to nearly 95% in the GWAS Catalog [22][23]. This imbalance reduces the accuracy of variant interpretation in individuals of non-European descent, leading to inconclusive results, a higher prevalence of variants of uncertain significance, and decreased predictive performance of polygenic risk scores [18][21].

Program Design and Governance

In Brazil, several factors have enabled the development of a long-term, sustainable public policy to advance precision public health, such as the presence of leading research groups in genomics and advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), the substantial decline in genomic sequencing costs, the growing expertise in managing large-scale health and genomic data, and the resilience of the public healthcare system.

GenBR brought together multiple stakeholders to establish a national strategy aimed at strengthening genomic and precision health research while promoting its practical application within SUS. This network include participants from different sectors within the MoH; the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation; referral hospitals participating in the SUS Institutional Development Support Program (In Portuguese: Programa de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Institucional do Sistema Único de Saúde, PROADI-SUS); academic institutions; science, technology and innovation institutions; Brazilian scientific societies; professional councils; ethics and regulatory bodies; research funding agencies; and the Pan American Health Organization of the World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO), among others.

Initially established by Ministerial Ordinance GM/MS No. 1,949 of August 4, 2020, GenBR aims to lay the foundation for genomics and precision health within SUS. Its primary goals include advancing science and technology countrywide, fostering the development of a national genomics industry, and conducting proof-of-concept studies to assess the practical application of precision health in public healthcare. To this end, the Program aimed to: develop a Brazilian reference genome; establish a national database of genomic and clinical data; strengthen scientific capacity and human capital in genomics and precision health; promote domestic production of genomic inputs and technologies; and train SUS professionals in precision health and genomics. GenBR is guided by principles such as evidence-based clinical practice, informed consent and participant autonomy, the right to health-related information, ethical standards and human dignity, non-discrimination, data confidentiality, and ethical, legal, and social responsibility for the knowledge generated.

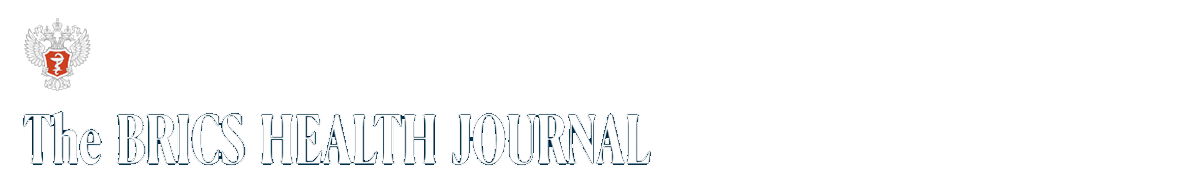

Almost five years later, the MoH decided to expanded and updated GenBR through Ordinance GM/MS No. 6,581 of January 29, 2025, introducing four additional goals: disseminating information to the public, encouraging research focused on the genetic diversity of the Brazilian population, strengthening innovation and production capabilities, and ensuring the continuous training of healthcare professionals. The MoH also broadened GenBR’s objectives to include the creation of a national biobank, promotion of collaboration among science, technology, and innovation institutions, expansion of shared scientific infrastructure, enhancement of ethical debate around genomics and precision public health, and fostering of knowledge translation. Figure 1 illustrates GenBR’s strategic pillars and updated objectives.

FIG. 1. Objectives of the Genomas Brasil Program according to Ordinance GM/MS No. 6,581/2025

The Ordinance GM/MS No. 6,581/2025 also established a new governance structure for the Program, composed of three primary levels: management level, led by the Secretariat for Science, Technology and Innovation in Health of the MoH (In Portuguese: Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação em Saúde do Ministério da Saúde, SCTIE/MS); coordination level, managed by the Department of Science and Technology (In Portuguese: Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia da SCTIE/MS, Decit/ SCTIE/MS) through the Executive Secretariat; and technical level, comprising the Technical Advisory Board (CTA-GenBR) and supporting thematic working groups. The CTA-GenBR is responsible for contributing to the formulation, review, and implementation of actions and strategies related to the operationalization of GenBR; supporting the execution and monitoring of the Program’s activities; and proposing priority topics for investment in scientific research focused on genomics and precision public health. The MoH also revised the Program’s official name to explicitly incorporate the term Precision Public Health, underscoring its commitment to population-level impact through targeted public policies.

GenBR builds its structure around six interconnected pillars that guide strategic actions and engage multiple stakeholders. Axis I – Processes and Regulations encompasses operational milestones, regulatory instruments, and technical guidelines, while Axis II – Scientific Capacity Building focuses on strengthening the national research infrastructure through public calls, targeted research commissions, and tax incentive contracts. It serves as the core of GenBR’s research agenda, generating scientific evidence to support the proof of concept for implementing precision health within the SUS. Axis III – Industrial Development addresses technological dependence and production vulnerabilities by fostering national capacity in the precision health sector. Axis IV – Human Capital Development promotes the training of researchers in precision health, aiming to build and retain national expertise. Finally, Axis V – Workforce focuses on establishing multiprofessional networks and residency programs in genetics and genetic counseling, whereas Axis VI – Knowledge Dissemination encompasses initiatives to share scientific and technological advances with the academic community, health professionals, and the broader society.

Under Strategic Axis I, the Program’s governance framework is structured to advance the internal regulatory ecosystem through the formulation of policies and guidelines. Key instruments under development include: the Intellectual Property Protection Policy, which governs rights over intellectual creations; the Policy on Scientific Publications and Dissemination, aimed at ensuring open access and transparency; the Technical Guideline for the Generation of Genomic and Phenotypic Data, focused on standardization and data quality; the Ethics Commitment Policy for research conducted under GenBR; and the Policy on Genomic Data Security, Access, and Use, which regulates access to the Program’s national genomic and clinical database. Together, these instruments are designed to ensure the standardization, transparency, and harmonization of research practices, enabling consistent, auditable management, storage, and data sharing protocols.

Alignment with national and international health policies and strategies

In Brazil, the National Policy for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health aims to promote sustainable national development by advancing scientific and technological knowledge that addresses the country’s economic, social, cultural, and political priorities. GenBR supports the implementation of this policy by engaging in various phases of the genomic research and application continuum, including large-scale sequencing and ATMPs. The program strategically targets key areas of public health, striking a balance between state-driven actions and independent scientific initiatives to ensure relevance, responsiveness, and inclusivity. Additionally, it enhances the societal value of genomics by producing data to inform evidence-based public health policies and by promoting participatory and transparent processes among stakeholders.

The Program aligns with the National Strategy for the Development of the CEIS, established by Decree No. 11,715/2023. Conceptually, the CEIS is a systemic space that integrates industrial and scientific subsystems with public health, reflecting a theoretical and political perspective that views economic development as intrinsically linked to the social and technological advancement of SUS [24]. This strategy aims to strengthen Brazil’s productive and technological capacities in health, reducing the SUS reliance on foreign technologies and expanding access to essential services and products. It encompasses sectors such as pharmaceuticals, biotechnologies, and medical devices. GenBR contributes to this strategy by reinforcing the national genomic infrastructure and enabling the development of biotechnology products and services based on domestic genomic data [25]. These actions can reduce import dependency and promote technological autonomy.

GenBR also aligns with the National Policy for the Comprehensive Care of People with Rare Diseases (In Portuguese: Política Nacional de Atenção Integral às Pessoas com Doenças Raras), established under Ordinance No. 199/2014. This policy aims to ensure timely access to diagnostic and therapeutic services for individuals affected by rare diseases within the SUS. The establishment of a Brazilian reference genome and a national repository of genomic and clinical data will allow the detection of disease-associated variants across diverse ancestral groups, helping to reduce diagnostic gaps and health disparities.

It is noteworthy the pivotal role played by Health Technology Assessment (HTA) in this process, serving as a bridge between scientific innovation and its safe and effective adoption within the public health system. HTA enables the evaluation not only of the clinical efficacy of personalized interventions but also of their cost-effectiveness and budgetary impact [26]. The use of biomarkers and genomics requires more robust and adaptable HTA protocols to keep pace with rapid technological advancements [27]. Consequently, there is a pressing need to strengthen the institutional and technical capacities of the National Committee for Health Technology Incorporation in SUS (In Portuguese: Comissão Nacional de Incorporação de Tecnologias no SUS in Portuguese, Conitec), particularly in developing specific assessment criteria for emerging precision health technologies that take into account the genetic diversity of the Brazilian population.

In addition, public health surveillance must be expanded to encompass genomic surveillance, pharmacogenomics, and molecular epidemiology, allowing for the monitoring of population-level risk patterns and treatment responses across subgroups [28]. In Brazil, pharmacogenomic surveillance has progressed through localized initiatives that combine genomic data collection with active monitoring of adverse drug reactions, contributing to improved prescribing safety within SUS [29]. However, LMICs continue to face challenges such as limited infrastructure, lack of technological tools for population-level monitoring, and the exclusion of population-specific variants from international guidelines [28].

At the international level, GenBR plays a critical role in promoting genomic equity by generating data that represent the genetic diversity of Brazil’s admixed population, thereby contributing to the global effort to include populations from the Global South in genomic research. By addressing this historical underrepresentation, the Program advances both scientific knowledge and equitable access to the benefits of precision medicine. Its commitments are in line with several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 10 (reduction of inequalities), SDG 3 (health and well-being through precision health), SDG 4 (training healthcare professionals in genomics), and SDG 9 (innovation and infrastructure development in science and technology).

In 2022, WHO issued a strategic document to promote equitable access to genomic technologies, with an emphasis on ethics, collaboration, and inclusion4. Building on this agenda, the PAHO/WHO, in partnership with Brazil’s MoH, convened a regional meeting in Brasília in 20245. The event aimed to disseminate the WHO’s strategy on genomics, exchange experiences and best practices, identify implementation barriers, and encourage regional cooperation. Outcomes included proposals to strengthen the genomics ecosystem in the Americas through resource mapping, creation of technical working groups, targeted communication strategies, sustainable financing, ethical data sharing, and capacity building using digital platforms.

Program Implementation and Outcomes

During its initial years of implementation, GenBR operated amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which exposed Brazil’s high dependency on imported molecular diagnostics and highlighted the urgency of strengthening domestic technological capabilities. As part of the national response, the Program supported the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (In Portuguese: Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Fiocruz) genomic surveillance network, which conducted representative sampling across all Brazilian regions to monitor SARS-CoV-2. This initiative involved partnerships with state public health laboratories, the General Coordination of Public Health Laboratories of the Secretariat for Health and Environmental Surveillance, and Decit/SCTIE/MS, facilitating the timely identification of variants and subvariants.

Considering these contributions, GenBR advanced its institutional partnerships, culminating in a Technical Cooperation Agreement between Decit/SCTIE/MS and Fiocruz. This agreement supported the launch of Public Call No. 2/2023 of the Inova initiative – Genome Sequencing, which aimed to expand genome sequencing services for humans and microorganisms of public health or biotechnological interest.

One of the key objectives of GenBR is to investigate the complexity of Brazil’s admixed population by sequencing the whole genomes of 100,000 individuals, sampled in proportion to the population distribution across the country’s five macro-regions. By August 2025, over 250 research projects had been funded across a range of areas, including oncological, rare, cardiovascular, infectious, neurological, and non-communicable diseases, as well as population genomics and precision health. Regarding gender equity, 56% of principal investigators are men and 44% are women.

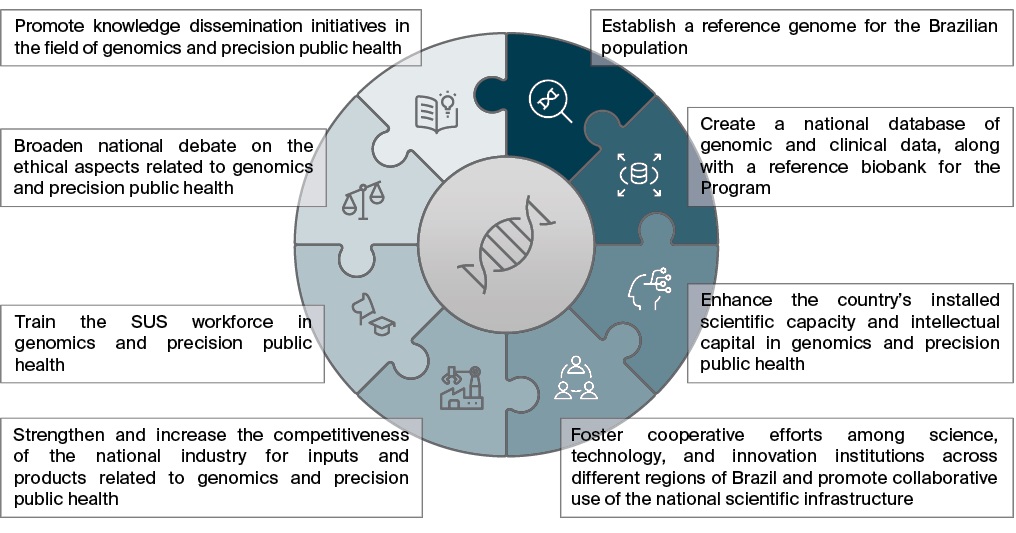

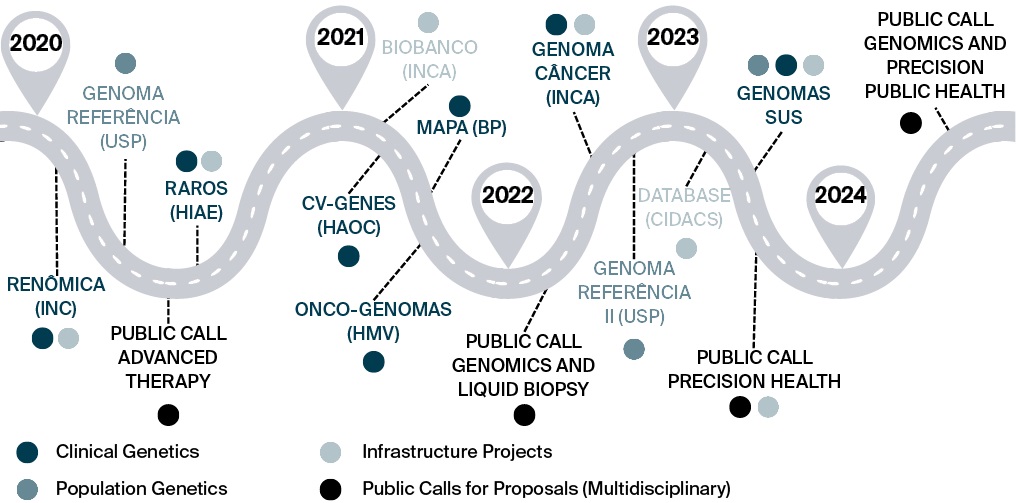

Figure 2 presents a timeline of GenBR’s major funded initiatives. By August 2025, financial investments had exceeded 1 billion Brazilian reals (BRL), supporting the sequencing of 67,000 samples. The MoH funded these projects either through direct contracting or via the PROADI-SUS, in which the MoH partners with selected hospitals to strengthen strategic initiatives within SUS. Nine large-scale genomics research projects associated with the Program have contributed to generating whole-genome data from 45,910 individuals. Among these, 4,427 (9.6%) are from the North, 8,103 (17.6%) from the Northeast, 24,743 (53.9%) from the Southeast, 6,899 (15.0%) from the South, and 1,738 (3.8%) from the Central-West region. Overall, 47% of the funded sequences are from population genomics projects, followed by studies focusing on cardiovascular diseases (19%) and rare diseases (18%) (Figure 3). The remaining genomes required to reach the target of 100,000 are currently under negotiation, and full funding is expected to be secured by the end of 2025.

FIG. 2. Timeline of key milestones and major projects of Genomas Brasil Program

Note: INC – National Institute of Cardiology (Instituto Nacional de Cardiologia); USP – University of São Paulo (Universidade de São Paulo); HIAE – Albert Einstein Israeli Hospital (Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein); INCA – National Cancer Institute (Instituto Nacional de Câncer); HAOC – Oswaldo Cruz German Hospital (Hospital Alemão Oswaldo Cruz); BP – Portuguese Beneficence Hospital (Beneficência Portuguesa); HMV – Moinhos de Vento Hospital (Hospital Moinhos de Vento); CIDACS – Center for Data and Knowledge Integration for Health (Centro de Integração de Dados e Conhecimentos para Saúde, Fiocruz Bahia); SUS – Unified Health System.

FIG. 3. Distribution of sequenced genomes funded by the Genomas Brasil Program according to research focus (updated in January 2025)

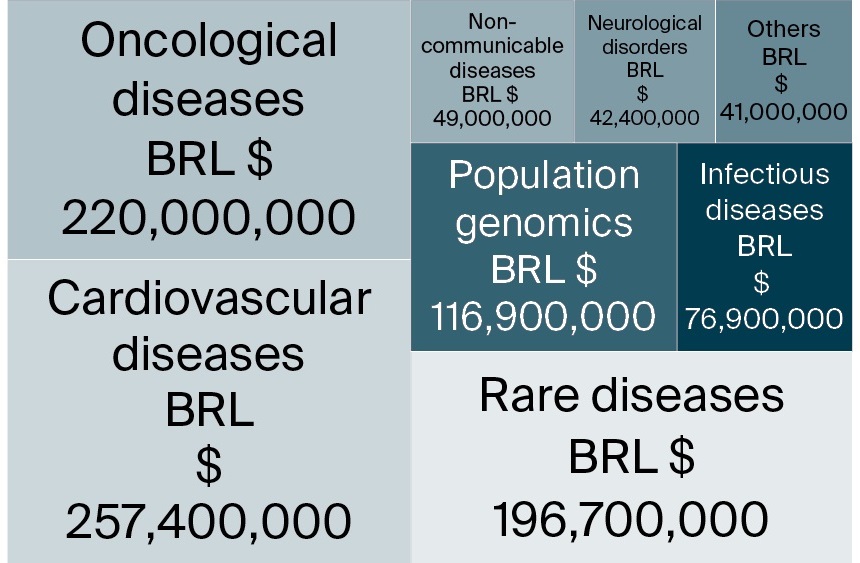

Figure 4 illustrates the allocation of financial resources across various health research domains. Cardiovascular diseases received the largest share of funding (257.4 million BRL), followed by oncological diseases (BRL 220 million) and rare diseases (BRL 196.7 million). Other areas of investment included population genomics (BRL 116.9 million) and infectious diseases (BRL 76.9 million). This distribution reflects national research priorities aimed at addressing high-burden diseases and advancing precision health strategies.

FIG. 4. Allocation of financial resources across strategic health areas within the Genomas Brasil Program

Note: BRL – Brazilian real.

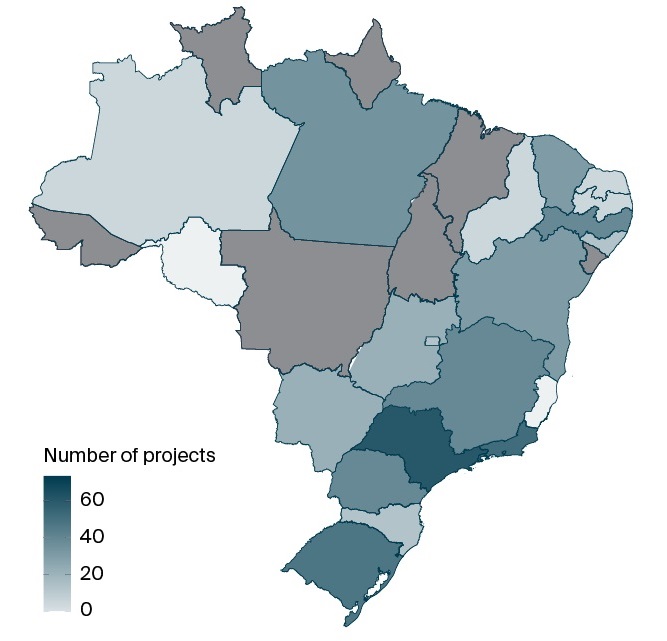

To date, 19 of the country’s 27 federative units have received funding. Of the supported projects, 60% originate from the Southeast, 16% from the South, 14% from the Northeast, and 5% each from the North and Central-West regions. Nevertheless, research in genomics and precision health remains heavily concentrated in Brazil’s Southeast region (Figure 5), consistent with long-standing national research patterns [30].

FIG. 5. The number of research projects by Brazilian state

Note: The count is based on the location of the Science and Technology Institution to which the project coordinator is affiliated.

To address the challenge of expanding scientific excellence beyond established centers, the Program’s updated Ordinance introduced measures to promote collaborative research networks. Additionally, beginning with the second Public Call, the MoH dedicated funding lines for early-career researchers (those who earned their PhD in the last decade) aiming to encourage research decentralization and reduce the dominance of long-established groups.

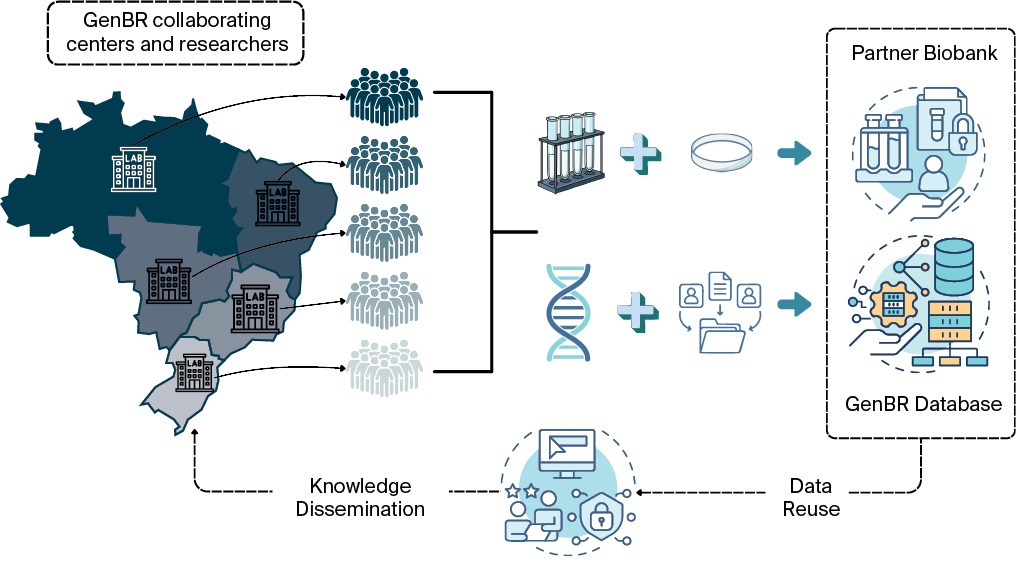

The large-scale sequencing initiatives supported by GenBR aim not only to investigate associations between genetic variation and health but also to generate extensive genomic, clinical, and sociodemographic data. To support the large volume of data generated and its translational potential for SUS, the Program established partnerships among universities, research institutes, and centers of excellence. In 2021, the MoH launched a project in partnership with the National Cancer Institute (In Portuguese: Instituto Nacional de Câncer, INCA) to create the GenBR biobank. In parallel, the MoH hired the Center for Data and Knowledge Integration for Health (In Portuguese: Centro de Integração de Dados e Conhecimentos para a Saúde, CIDACS), part of Fiocruz/Bahia, to design the national genomic and clinical data repository (GenBRdb), which is now in its final planning stages.

The GenBRdb architecture will consist of three functional layers: a data storage repository; a management platform; and an analytical environment. Raw sequences, phenotypic data, and metadata will be transferred to regional repositories, with storage solutions optimized for each data type to enhance performance, resilience, and fault tolerance. The management layer will act as middleware, coordinating data flow between the repositories and the analytical environment while centralizing access control, user and project management, consent tracking, and providing audit and traceability services. The analytical layer will host a portfolio of bioinformatics and machine learning tools, deployed on both specialized and general-purpose cloud platforms, enabling researchers to perform advanced analyses on authorized datasets without direct access to the underlying storage infrastructure.

In its initial phase, the system will store raw genomic and clinical data from 100,000 Brazilian individuals, requiring petabyte-scale infrastructure. Conceived as a discovery platform for precision health, GenBRdb is expected to be integrated into the National Health Data Network (In Portuguese: Rede Nacional de Dados em Saúde, RNDS), ensuring that research participants, patients, and healthcare professionals benefit from the results in compliance with prevailing ethical, legal, and social standards. In the future, with this structure, collaborating researchers from various regions of Brazil will be able to collect biological samples from diverse populations and send them to a facility partner for sequencing and secure storage. The resulting genomic datasets, linked to relevant clinical metadata, will be integrated into GenBRdb. Both the biological samples and data will be available for reuse, enabling other researchers to conduct further studies (Figure 6).

FIG. 6. Integrated workflow for genomic data collection, processing, and use in the Genomas Brasil Program

Note: GenBR – National Genomics and Precision Public Health Program; GenBR Database – the national genomic and clinical data repository.

Coordinated efforts are underway to ensure the secure exchange of data across health, research, and surveillance networks, in strict compliance with Brazil’s General Law for the Protection of Personal Data (In Portuguese: Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados Pessoais, LGPD), and to promote interoperability with national information systems and the RNDS. Once integrated, standardized, and made available following ethical and legal principles, these data can serve as a valuable resource for future research and inform evidence-based public policy.

Another key component of GenBR is the expansion of regional partnerships and the development of multiprofessional training networks through residency programs in Genetics and Genomics and Genetic Counseling. The pedagogical design of these programs was developed in collaboration with a group of specialists. Educational and research institutions will submit their proposals, and those selected will be able to offer multiprofessional residencies starting in 2026. Additionally, to promote knowledge dissemination in genomics and precision health, the MoH organized three virtual editions of the Genomas Brasil International Summit on Precision Health. These events convened representatives from academia, government, industry, and international initiatives to exchange knowledge and discuss recent scientific and technological advances in the field, with a particular focus on their integration into Brazil’s SUS. Together, these strategies are essential for strengthening local capacities and building a specialized workforce, thereby promoting inclusion and equitable access to precision health.

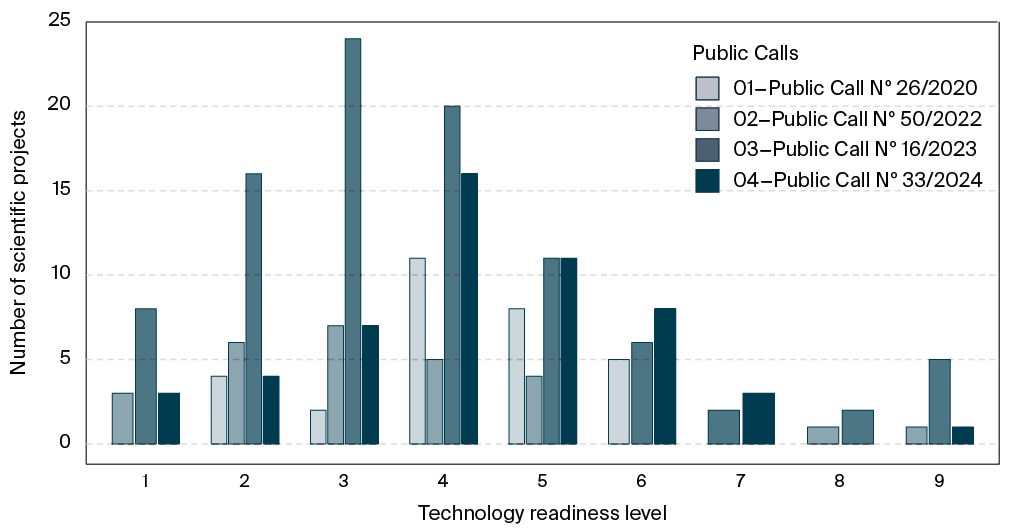

GenBR has supported research through public calls for proposals, allowing for wide competition among submissions and enhancing equity in the selection process. Over the past five years, nearly one major call has been launched annually in partnership with the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (In Portuguese: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, CNPq), except for 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In total, four public calls have selected 209 research projects led by institutions located across all regions of Brazil. Most of the funded projects fall within Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) 3 and 4, as assessed during the proposal submission phase (Figure 7)6. TRL 3 corresponds to the experimental proof of concept, marking the start of applied research and early-stage prototyping to assess feasibility and risks, whereas TRL 4 entails process refinement, comprehensive documentation, and validation at the laboratory scale.

FIG. 7. Distribution of technology readiness levels among projects selected through public calls promoted by the Genomas Brasil Program

Beyond supporting structural projects such as large-scale genomics, the implementation of precision public health requires an integrated, multidisciplinary approach, including research in genetic testing, biosensors, and cell and gene therapies7 [31][32]. Overall, GenBR has funded 111 projects related to ATMP development, with a total investment of BRL 327.9 million. The scale-up of ATMPs under good manufacturing practices (GMP) remains costly and technologically complex, particularly for LMICs, which often lack biomanufacturing infrastructure for producing critical inputs such as viral vectors and cloning plasmids [33]. This limitation is evident in the results of Public Call No. 26/2020, dedicated exclusively to supporting ATMP development: the highest TRL achieved among all funded projects was 6, underscoring the challenges of advancing to later stages that require GMP-grade production for clinical testing (Figure 7).

To prepare the country for the future integration of genomic and precision public health services into the SUS, GenBR funded five high-throughput sequencing platforms. This sequencing infrastructure will help reduce the backlog of genetic testing in Brazil, particularly for rare diseases, while simultaneously building national genomic capabilities across research institutions. Both physical infrastructure and technical expertise, from wet lab processes to data analysis, are crucial to ensuring national sovereignty, particularly for LMICs.

Since 2020, Brazil has made notable progress in strengthening its national capacity for manufacturing ATMP, particularly driven by research, development, and innovation demands emerging from projects supported by GenBR. The Fiocruz/Rio de Janeiro, leveraging investments from the CEIS, is preparing to begin producing key inputs, such as lentiviral and adeno-associated viral vectors, by repurposing infrastructure previously dedicated to the manufacturing of COVID-19 vaccines based on viral vector platforms [34].

In addition, the MoH financed a Center of Excellence in Advanced Therapies (CCTA), which was selected through a public call launched in partnership with the Brazilian Company for Research and Industrial Innovation (In Portuguese: Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa e Inovação Industrial, EMBRAPII). Located at the Albert Einstein Hospital in São Paulo, the CCTA aims to expand national capabilities in the field of advanced therapies, specifically gene therapy, cell therapy, and tissue engineering. Its mission includes fostering the domestic production of ATMPs, attracting companies from the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors, and training highly qualified professionals to support the growth of this strategic area.

In December 2023, the MoH established a formal partnership with the Ribeirão Preto Medical School of the University of São Paulo to launch an academic network focused on characterizing genomic factors influencing health and disease processes in the Brazilian population. This initiative, titled Genomas SUS, is currently in its initial phase, with an investment exceeding BRL 90 million to support the sequencing of 21,000 genomes. Ensuring sample representativeness is a strategic priority, with an emphasis on the inclusion of diverse ethno-racial groups, particularly those historically underrepresented in genomic research. The project is coordinated through a robust network of eight anchor centers strategically distributed across all major regions of the country. It involves leading institutions such as Fiocruz (Pernambuco and Paraná), the University of São Paulo, and the Federal Universities of Minas Gerais, Pará, and Rio de Janeiro, alongside collaborating centers in 16 Brazilian states. A key pillar of the initiative is the integration of major national cohorts, diverse in both design and population composition. To date, samples from 15 cohort studies have been included in the project, such as SABE [35], EPIGEN [36], and BRISA [37].

Lessons learned and insights for BRICS and Latin American countries

Over its five-year trajectory, GenBR has emerged as one of the most significant large-scale genomics and precision health initiatives for public health in the Global South8 [38][39]. One of the key lessons lies in the role of sustained political will, as evidenced by continued financial support from the MoH, and the definition of clear strategic objectives. These include the generation of representative genomic data, the advancement of domestic technological capabilities, and the integration of genomic knowledge into the public health system, particularly in healthcare delivery and epidemiological surveillance. This political commitment, combined with the coordination of multiple institutions, including universities, INCA, Fiocruz, and regional research centers, has enabled the development of robust infrastructures, such as biobanks and national data repositories, multiprofessional networks, and governance and ethical frameworks tailored to Brazil’s population diversity and public health needs [18][40].

A long-term vision is also reflected in the Program’s strategic planning for the progressive expansion of sequencing coverage, the standardization of protocols, and the dissemination of results. For regional scalability and adaptation, several enabling conditions must be emphasized: sustained public investment and partnership mechanisms, including international collaboration and alignment with regional initiatives such as the Genetics of Latin American Diversity (GLAD) [38]; adequate physical and computational infrastructure for the storage, curation, analysis, and sharing of genomic and clinical data; interoperability frameworks between national databases and regional health surveillance systems; inclusive policies and protocols that ensure the effective representation of historically marginalized populations, while respecting cultural specificities and ensuring social and scientific benefits to participating communities; and incentives for researcher training, professional network development, and cross-country exchange of methodologies and experiences.

Strengthening regional cooperation through the creation of consortia in Latin American countries is pivotal to promoting shared technical standards, infrastructure, anonymized data, and best practices in ethical governance, an approach that could also be extended to BRICS countries. Additional recommendations include fostering regional training in the areas of bioinformatics and research ethics; adopting policies that ensure equitable access to the benefits of genomic medicine while avoiding new forms of value extraction or technological dependency; and supporting structured dialogue platforms that bring together governments, researchers, and civil society to align priorities, assess impacts, and disseminate lessons learned.

The experiences of China and India in developing ATMPs also provide key insights for other BRICS and Latin America countries. China has emerged as a global leader, propelled by strategic policies such as the 13th and 14th Five-Year Plans, which prioritized investment in genomics and biotechnology to reduce foreign dependency [41]. India has demonstrated that public-private partnerships can facilitate the development of affordable, locally developed chimeric antigen receptor T-cells (CAR-T) therapies. In 2023, it secured approval for a CAR-T treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia at a cost of 36,000 to 42,000 United States dollars per patient, roughly ten times less than equivalent therapies approved in Brazil. These examples demonstrate how long-term planning, adaptive regulation, and strategic collaboration can foster innovation while enhancing access to ATMPs [42].

Conclusion

By combining a dedicated budgetary structure, governance arrangements that integrate academia, industry, and policymakers, and an industrial strategy focused on technological sovereignty, GenBR transcends the scope of individual research projects to become a state-led instrument for scaling precision public health within a universal health system. While training a highly skilled workforce and fostering positive spillovers for the knowledge economy, the Program also contributes to reducing dependence on critical imported inputs. In doing so, it lays the foundation for a sustainable innovation cycle in which scientific value, clinical impact, and fiscal resilience continuously and strategically reinforce one another.

The evolution of public genomics policies in Brazil has emerged as a key driver of health innovation, with direct implications for promoting equity and transforming healthcare delivery. GenBR exemplifies this progress by integrating genomics into SUS through coordinated actions in research, capacity building, and technological development. This initiative positions Brazil as an international reference, demonstrating that it is possible to implement large-scale strategies for personalized medicine and early diagnosis even in settings characterized by population diversity and regional inequalities. The integration of genomic data from historically underrepresented populations not only enhances the applicability of scientific findings to the national context but also fuels the health innovation ecosystem, creating opportunities for more inclusive and effective solutions. In this context, genomics emerges not merely as a scientific tool, but as a strategic instrument for transforming Brazil’s SUS.

1. Brasil. Ministry of Health. Secretariat of Science, Technology and Strategic Inputs. Department of Science and Technology. [National Policy on Science, Technology and Innovation in Health]. (In Portuguese). 2nd ed. Publishing House of the Ministry of Health; 2008:44. Accessed 22.10.2025. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/Politica_Portugues.pdf

2. Bardin L. Análise de Conteúdo [Content Analysis]. (In Portuguese). Editions 70; 2015. Accessed 22.10.2025. https://madmunifacs.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/anc3a1lise-de-contec3bado-laurence-bardin.pdf

3. Salzano FM, Bortolini MC. The Evolution and Genetics of Latin American Populations. Cambridge University Press; 2002. Accessed 22.10.2025. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/evolution-and-genetics-of-latin-american-populations/FF88CBA48DD870467BD3E379039E41A8

4. World Health Organization. Accelerating access to genomics for global health: promotion, implementation, collaboration and ethical, legal and social issues. WHO; 2022:46. Accessed 22.10.2205. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240052857

5. Pan American Health Organization. Human genomics for health: Enhancing the impact of effective research. Report of the first regional meeting for the Americas. Brasília, 15–16 May 2024. PAHO; 2024:36. Accessed 22.10.2025. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/62584

6. Board on Health Sciences Policy; Board on Life Sciences; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Technologies to Enable Autonomous Detection for BioWatch: Ensuring Timely and Accurate Information for Public Health Officials – Workshop Summary. National Academies Press (US); 2013. Accessed 22.10.2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201359/

7. DeNegri F. Políticas públicas para ciência e tecnologia no Brasil: cenário e evolução recente [Public policies for science and technology in Brazil: current scenario and evolution]. (In Portuguese). Institute for Applied Economic Research – IPEA; 2021:19. Accessed 22.10.2025. https://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/items/16ae232c-1e87-4c61-a9ee-b6d5468c24c7

8. World Health Organization. Accelerating access to genomics for global health: promotion, implementation, collaboration and ethical, legal and social issues. WHO; 2022:46. Accessed 22.10.2205. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240052857

References

1. Vasconcelos AMN, Gomes MMF. Transição demográfica: a experiência brasileira [Demographic transition: the Brazilian experience]. (In Portuguese). Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2012;21(4):539–548. doi:10.5123/S1679-49742012000400003

2. Cohen RV, Drager LF, Petry TBZ, Santos RD. Metabolic health in Brazil: trends and challenges. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(12):937–938. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30370-3

3. Nunes K, Araújo Castro E Silva M, Rodrigues MR, et al. Admixture’s impact on Brazilian population evolution and health. Science. 2025;388(6748):eadl3564. doi:10.1126/science.adl3564

4. Félix TM, Fischinger Moura de Souza C, Oliveira JB, et al. Challenges and recommendations to increasing the use of exome sequencing and whole genome sequencing for diagnosing rare diseases in Brazil: an expert perspective. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22(1):11. doi:10.1186/s12939-022-01809-y

5. Pimentel FG, Buchweitz C, Campos RTO, Hallal PC, Massuda A, Kieling C. Realising the future: Health challenges and achievements in Brazil. SSM – Mental Health. 2023;4:100250. doi:10.1016/j.ssmmh.2023.100250

6. Castro E Silva MA, Ferraz T, Couto-Silva CM, et al. Population Histories and Genomic Diversity of South American Natives. Mol Biol Evol. 2022;39(1):msab339. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab339

7. Naslavsky MS, Scliar MO, Yamamoto GL, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of 1,171 elderly admixed individuals from São Paulo, Brazil. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1004. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28648-3

8. Hou K, Bhattacharya A, Mester R, Burch KS, Pasaniuc B. On powerful GWAS in admixed populations. Nat Genet. 2021;53(12):1631-1633. doi:10.1038/s41588-021-00953-5

9. Collins FS, Fink L. The Human Genome Project. Alcohol Health Res World. 1995;19(3):190–195.

10. Turnbull C, Scott RH, Thomas E, et al. The 100000 Genomes Project: bringing whole genome sequencing to the NHS. BMJ. 2018;361:k1687. doi:10.1136/bmj.k1687

11. Ramirez AH, Sulieman L, Schlueter DJ, et al. The All of Us Research Program: Data quality, utility, and diversity. Patterns (N Y). 2022;3(8):100570. doi:10.1016/j.patter.2022.100570

12. PFMG2025 contributors. PFMG2025-integrating genomic medicine into the national healthcare system in France. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2025;50:101183. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.101183

13. Zayed H. The Qatar genome project: translation of whole-genome sequencing into clinical practice. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70(10):832–834. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12871

14. Stark Z, Boughtwood T, Haas M, et al. Australian Genomics: Outcomes of a 5-year national program to accelerate the integration of genomics in healthcare. Am J Hum Genet. 2023;110(3):419–426. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.01.018

15. Alrefaei AF, Hawsawi YM, Almaleki D, Alafif T, Alzahrani FA, Bakhrebah MA. Genetic data sharing and artificial intelligence in the era of personalized medicine based on a cross-sectional analysis of the Saudi human genome program. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1405. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05296-7

16. Li Z, Jiang X, Fang M, et al. CMDB: the comprehensive population genome variation database of China. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D890–D895. doi:10.1093/nar/gkac638

17. Kurki MI, Karjalainen J, Palta P, et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a wellphenotyped isolated population. Nature. 2023;613(7944):508–518. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05473-8

18. Jiwani T, Akinwumi A, Cheé-Santiago J, et al. Conceptualizing the public good for genomics in the global South: a cross-disciplinary roundtable dialogue. Front Genet. 2025;16:1523396. doi:10.3389/fgene.2025.1523396

19. Rocha CS, Secolin R, Rodrigues MR, Carvalho BS, Lopes-Cendes I. The Brazilian Initiative on Precision Medicine (BIPMed): fostering genomic data-sharing of underrepresented populations. NPJ Genom Med. 2020;5:42. doi:10.1038/s41525-020-00149-6

20. Howley C, Haas MA, Al Muftah WA, et al. The expanding global genomics landscape: Converging priorities from national genomics programs. Am J Hum Genet. 2025;112(4):751–763. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2025.02.008

21. Ojewunmi OO, Fatumo S. Driving Global Health equity and precision medicine through African genomic data. Hum Mol Genet. 2025. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddaf025

22. Mills MC, Rahal C. The GWAS Diversity Monitor tracks diversity by disease in real time. Nat Genet. 2020;52(3):242–243. doi:10.1038/s41588-020-0580-y

23. Troubat L, Fettahoglu D, Henches L, Aschard H, Julienne H. Multi-trait GWAS for diverse ancestries: mapping the knowledge gap. BMC Genomics. 2024;25(1):375. doi:10.1186/s12864-024-10293-3

24. Gadelha CA, Maretto G, Nascimento MA, Kamia F. The health economic-industrial complex: production and innovation for universal health access, Brazil. Bull World Health Organ. 2024;102(5):352–356. doi:10.2471/BLT.23.290838

25. Gadelha CA. Desenvolvimento, complexo industrial da saúde e política industrial [Development, health-industrial complex and industrial policy]. (In Portuguese). Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40 Spec no.:11–23. doi:10.1590/s0034-89102006000400003

26. Borges S, Rodrigues F, Pires W, et al. PP19 Health Technology Assessment Reports In Brazilian Unified Health System: Number Of Potential Beneficiaries in 2022. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2023;39(Suppl 1):S57. doi:10.1017/S0266462323001769

27. Love-Koh J, Peel A, Rejon-Parrilla JC, et al. The Future of Precision Medicine: Potential Impacts for Health Technology Assessment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(12):1439–1451. doi:10.1007/s40273-018-0686-6

28. Borbón A, Briceño JC, Valderrama-Aguirre A. Pharmacogenomics Tools for Precision Public Health and Lessons for Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2025;18:19–34. doi:10.2147/PGPM.S490135

29. Suarez-Kurtz G, Kovaleski G, Elias AB, et al. Implementation of a pharmacogenomic program in a Brazilian public institution. Pharmacogenomics. 2020;21(8):549–557. doi:10.2217/pgs-2020-0016

30. Sidone OJG, Haddad EA, Mena-Chalco JP. A Ciência nas Regiões Brasileiras: Evolução da Produção e das Redes de Colaboração Científica [Science in Brazilian regions: Development of scholarly production and research collaboration networks]. (In Portuguese). Transinformação. 2016;28(1):15–31. doi:10.1590/2318-08892016002800002

31. Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):793–795. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1500523

32. Hartl D, de Luca V, Kostikova A, et al. Translational precision medicine: an industry perspective. J Transl Med. 2021;19(1):245. doi:10.1186/s12967-021-02910-6

33. Sachetti CG, Barbosa A Jr, de Carvalho ACC, Araujo DV, da Silva EN. Challenges and opportunities for access to Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products in Brazil. Cytotherapy. 2024;26(8):939–947. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2024.03.492

34. Morales Saute JA, Picanço-Castro V, de Freitas Lopes AC, et al. Clinical trials to gene therapy development and production in Brazil: a review. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2025;43:100995. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2025.100995

35. Albala C, Lebrão ML, León Díaz EM, et al. Encuesta Salud, Bienestar y Envejecimiento (SABE): metodología de la encuesta y perfil de la población estudiada [The Health, Well-Being, and Aging (“SABE”) survey: methodology applied and profile of the study population]. (In Spanish). Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;17(5–6):307–322. doi:10.1590/s1020-49892005000500003

36. Lima-Costa MF, Macinko J, Mambrini JV, et al. Genomic Ancestry, Self-Rated Health and Its Association with Mortality in an Admixed Population: 10 Year Follow-Up of the Bambui-Epigen (Brazil) Cohort Study of Ageing. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144456. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144456

37. Confortin SC, Ribeiro MRC, Barros AJD, et al. RPS Brazilian Birth Cohorts Consortium (Ribeirão Preto, Pelotas and São Luís): history, objectives and methods. Cad Saude Publica. 2021;37(4):e00093320. doi:10.1590/0102-311X00093320

38. Borda V, Loesch DP, Guo B, et al. Genetics of Latin American Diversity Project: Insights into population genetics and association studies in admixed groups in the Americas. Cell Genom. 2024;4(11):100692. doi:10.1016/j.xgen.2024.100692

39. Fatumo S, Yakubu A, Oyedele O, et al. Promoting the genomic revolution in Africa through the Nigerian 100K Genome Project. Nat Genet. 2022;54(5):531–536. doi:10.1038/s41588-022-01071-6

40. Madden EB, Hindorff LA, Bonham VL, et al. Advancing genomics to improve health equity. Nat Genet. 2024;56(5):752–757. doi:10.1038/s41588-024-01711-z

41. Hu Y, Feng J, Gu T, et al. CAR T-cell therapies in China: rapid evolution and a bright future. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(12):e930–e941. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00291-5

42. Doxzen KW, Adair JE, Fonseca Bazzo YM, et al. The translational gap for gene therapies in low- and middle-income countries. Sci Transl Med. 2024;16(746):eadn1902. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.adn1902

About the Authors

Giovanny Vinícius Araújo de FrançaBrazil

Giovanny Vinícius Araújo de França, PhD, Technologist, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science,Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil, SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Evandro de Oliveira Lupatini

Brazil

Evandro de Oliveira Lupatini, PhD, Technologist, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil, SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Rodrigo Theodoro Rocha

Brazil

Rodrigo Theodoro Rocha, MSc, Technical Consultant, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil, SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Rafaela de Cesare Parmezan Toledo

Brazil

Rafaela de Cesare Parmezan Toledo, PhD, Technical Consultant, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil; SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Graziella Santana Feitosa Figueiredo

Brazil

Graziella Santana Feitosa Figueiredo, PhD, Technical Consultant, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil; SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Carlos Eduardo Ibaldo Gonçalves

Brazil

Carlos Eduardo Ibaldo Gonçalves, PhD, Technical Consultant, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil; SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health,

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Isis Laynne de Oliveira Machado

Brazil

Isis Laynne de Oliveira Machado, PhD, Technical Consultant, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil; SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Ana Paula Anzolin

Brazil

Ana Paula Anzolin, PhD, Technical Consultant, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil; SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Carolina Carvalho Gontijo

Brazil

Carolina Carvalho Gontijo, PhD, Technical Consultant, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil; SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Julia Freitas Daltro Vidal

Brazil

Julia Freitas Daltro Vidal, PhD, Technical Consultant, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil; SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Andréa Leite Ribeiro

Brazil

Andréa Leite Ribeiro, PhD, Technical Consultant, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil; SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Meiruze Sousa Freitas

Brazil

Meiruze Sousa Freitas, Specialist in Health Regulation and Sanitary Surveillance, Director, Department of Science and Technology of the Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil; SRTVN PO700 – Ministry of Health

Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, 70655-775

Fernanda De Negri

Fernanda De Negri, PhD, Secretary, Secretariat for Science, Technology, and Innovation in Health, Ministry of Health, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil

Esplanade of Ministries, Block “G”, 8th floor, CEP: 70058-900

Review

For citations:

Araújo de França G., Lupatini E., Rocha R., Toledo R., Figueiredo G., Gonçalves C., Machado I., Anzolin A., Gontijo C., Vidal J., Ribeiro A., Freitas M., De Negri F. Five years of the Genomas Brasil Program: advancing genomics and precision health within Brazil’s unified health system. The BRICS Health Journal. 2025;2(3):41-59. https://doi.org/10.47093/3034-4700.2025.2.3.41-59

JATS XML